Rising Red Lotus

“There’s No Way That I’m Going Backwards”

Rising Red Lotus Opens Up About His Creative Process, Getting Sober, and Growing Up As a Biracial Child in Atlanta

Text: Gino Sorcinelli

Photgraphy: Antonio Francisco

Thirty-two-year-old Atlanta native Brandon Sadler has earned reverence from critics and peers alike with his work as an artist, calligrapher, film director, painter, and writer. Better known to the world by his artist moniker Rising Red Lotus, he is a gifted visual storyteller whose work often reflects the “universal human condition” while examining ideas of change, cultural connectivity, and a variety of other topics.

After earning his bachelor of fine arts degree in painting and illustration in 2009 from Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) Atlanta, Rising Red Lotus’ work has become a staple at Atlanta art galleries such as High Museum of Art and Mason High Art. Well-known for awe-inspiring public murals, his art is also a highly sought after commodity for private collections. In addition to his success with group and solo exhibitions, Riding Red Lotus boasts a client list with names including Allstate, Converse, Google, NBC, Red Bull, and Universal.

Rising Red Lotus’ most recent feat was having his artwork featured in Marvel Studios’ critically acclaimed blockbuster Black Panther, the highest-grossing film of 2018 and the fourth highest-grossing film ever in the US. His intricate graffiti mural served as a focal point in superhero Shuri’s lab.

With the film still performing well at theaters around the country, Rising Red Lotus took a break from answering work emails in an Atlanta coffee shop to talk about the origins of his name, his time in South Korea, his affinity for tea, and his connection to the praying mantis.

Gino Sorcinelli: From what I’ve read, you’re on another level than most tea drinkers. Since you’re working out of a coffee shop today, I’m curious if you’re drinking tea right now.

Rising Red Lotus: Yeah, I actually am. (Laughs) Right now I’m at a coffee shop and I can’t bring out my fancy stuff here, so I’m drinking Dragonwell. It’s a green tea, I guess the formal name is lung ching. It tastes pretty good, it’s nice and sweet.

GS: What made you first start out on the journey of really diving into tea?

RRL: I like to nerd out on stuff and it’s a wealth of knowledge to learn about tea and the culture around it. It’s not just a beverage. It’s a way of life, philosophy, and gateway to parts of yourself. I had started going to get sober. I don’t know if you’ve ever abstained from anything in particular, but when you do it, you reach for things that kind of distract you from what you’re trying to get away from. I was finding that the things I was reaching for were just new vices and they were numbing me from fixing what caused me to have vices in the first place.

Somehow I came across tea through researching some YouTube stuff about different landscape painting techniques. A Chinese tea ceremony came up and I just started looking into it more. I’m super process driven and like things that have multiple parts or some kind of ritual. I started researching more tea and drinking and learning how to brew and getting into the way of it. I found that as opposed to being a distraction from what I was trying to get away from, it gave me space to actually understand what was affecting me and why I was doing what I used to do. It has a really good way of putting you in the present moment.

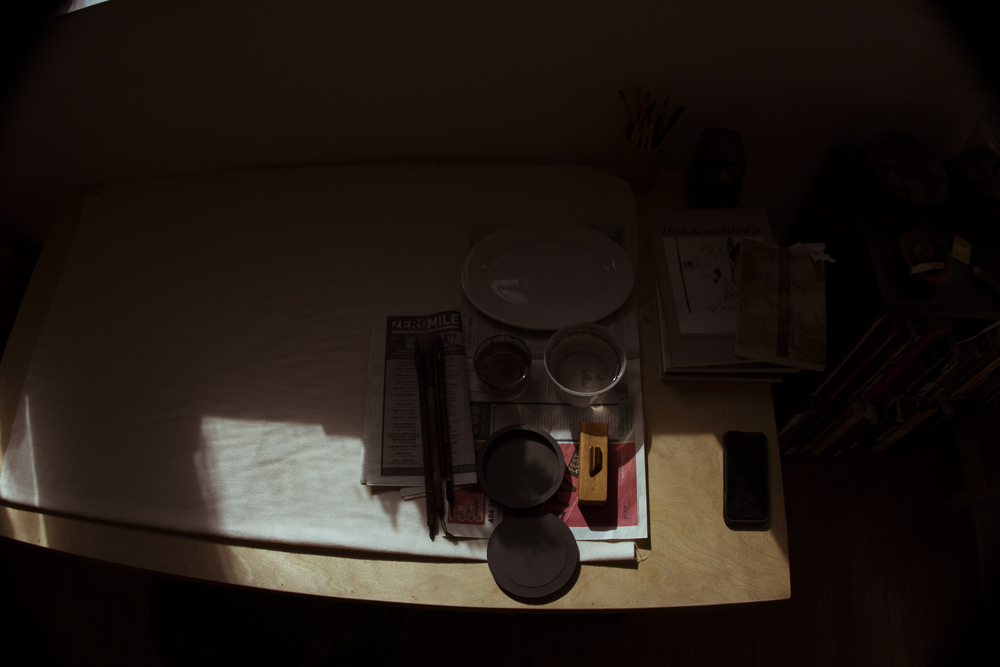

GS: Many creators have a ritualized aspect to their work. Do you feel like tea has become an integral part of your creative process too?

RRL: It’s becoming that way. For about a year now I drink tea every single day. The way that I create, the steps taken to get to the end result are on the forefront and as important if not more important than the end result. It’s the same way with tea. The whole process is you’re drinking tea before it ever even enters your cup.

GS: Switching gears a bit, when do you think your identity as Rising Red Lotus first started to form?

RRL: That came up before I went to Korea. I was an only child, so I was always pretty introspective and had a lot of time to contemplate existential concepts. When I was in college we had a self-promotion class where you had to come up with a logo and develop business cards and that kind of stuff. I was like, “Alright, I want something that I can identify with past this class. I want something that can grow as I grow as a person.”

In the things that I was reading and absorbing, the symbolism behind the lotus kept coming up. I was reading a lot of Hindu-related things and Buddhism-related things. Siddhartha was a really big book for me at that time and so was The Alchemist. So the lotus just kind of spoke out to me. I was thinking about metaphors for life being like we live in this swamp and it’s a balance of positive and negative influences, nutrients. You kind of sow your roots into the very bottom of it, gain insights from both sides, and rise to the surface to become whatever it is you’re going to be. That’s where that came from. The “red” bit of it was more like Chakra symbolism. My incarnation color is red Chakra, which is the root Chakra—where everything springs from. It just kind of all fell into place symbolically, so I put it all together that way.

GS: It seems like the lotus flower symbolism embraces this mix of both good and bad within all of us. It’s not something that we should be afraid of, but instead learn to deal with and accept our darker and less pleasant aspects as well as the good ones.

RRL: Yeah, definitely. Just to use as an example, I’m two years sober. Well, those experiences and that side of me—I can’t wash them clean from the record. It’s more so that I’m aware of them, I know how to live with them now, and they still exist. Those things, had I not gone through them, I might not have some of the world perspective and I might not have some of the development that I’ve been able to grasp onto. I don’t think there is a good or a bad, it’s just all thrown together in that water.

It’s not as a simple as, this person is out there on a mountaintop and they’re all enlightened and all that. The journey is so much more beautiful. To me, nobody is born on the mountaintop and they have everything together. To me, that person that was down and out and doing some messed up (things). Now they understand why that was happening and a new way to do it. That is more important to me.

GS: How has sobriety influenced and changed your artwork? Also, I’m also curious if you now allow yourself to do any other substances outside of drinking.

RRL: I’m completely sober. I was doing all kinds of stuff in those times and that went on for about 12-13 years. I was highly functional, doing what I needed to do, excelling in my career, and producing all the work people have seen from me in the midst of being super depressed and self-destructive. Upon getting to a state of clarity and not doing any of that stuff anymore, my mind is clear and my thoughts are more directive. I’ve always felt connected to my work, but now I feel that it comes from a more grounded place.

I also discovered that some of the reasons why I was doing these things had more to do with internal mental issues and I guess social things I was dealing with and less, “I’m doing this so I can be creative.” These other things were just to pass the time because I was bored and running from some stuff. Fortunately, it didn’t destroy me.

But it never really had a negative effect on my work. I could be up until six in the morning doing whatever and then be ready at eight in the morning to go do a mural with kids for Allstate—which actually happened. (Laughs) I don’t know. I mean, I always had the passion to do what I’m here to do but I also was wilding out a little bit.

GS: Battling addiction and maintaining sobriety is not easily achieved by most people. Did you ever relapse during the process?

RRL: Well, I went about seven months at the end of 2014 and then I relapsed really hard. And then went maybe three or four months after that and then got back on track at the end of 2016. It’s been pretty smooth ever since. I can confidently say that there’s no way that I’m going backwards.

GS: What do you think were some of the things driving the substance abuse?

RRL: I think one, for a creative, depending on the path that you take, you end up in situations where you’re isolated a long time to get your work done. For my case, I worked all day and everybody else was at whatever job. So the only time I was able to see people was at night. At night time, you’re gonna go eat, maybe go to a movie, but likely you’ll go to a bar. There’s not very many options for what you’re gonna do to entertain yourself. If you already have a history of intake or consumption, then you’re gonna really go in.

I already had an upbringing where since the age of 12 I was smoking, drinking, doing all kinds of (things). It just kind of progressed as I got into adulthood. Plus I was dealing with some anger issues from childhood stuff and general depression from some unresolved relationship (issues). I was just feeling mentally and spiritually isolated because all of these environments I was putting myself in.

GS: Now that you’ve been sober for a couple of years, what’s the emotional tenor of the work that you’re inspired to make?

RRL: Sometimes it’s very light, sometimes it’s introspective and moody, sometimes it’s lovesick—it’s all of those things, man. I’ve diversified myself to be less governed by, “Oh, I’m a painter” and more governed by “Oh, this is where I’m at energetically so I’m going to make these things.”

GS: Battling addiction and maintaining sobriety is not easily achieved by most people. Did you ever relapse during the process?

RRL: Well, I went about seven months at the end of 2014 and then I relapsed really hard. And then went maybe three or four months after that and then got back on track at the end of 2016. It’s been pretty smooth ever since. I can confidently say that there’s no way that I’m going backwards.

GS: What do you think were some of the things driving the substance abuse?

RRL: I think one, for a creative, depending on the path that you take, you end up in situations where you’re isolated a long time to get your work done. For my case, I worked all day and everybody else was at whatever job. So the only time I was able to see people was at night. At night time, you’re gonna go eat, maybe go to a movie, but likely you’ll go to a bar. There’s not very many options for what you’re gonna do to entertain yourself. If you already have a history of intake or consumption, then you’re gonna really go in.

I already had an upbringing where since the age of 12 I was smoking, drinking, doing all kinds of (things). It just kind of progressed as I got into adulthood. Plus I was dealing with some anger issues from childhood stuff and general depression from some unresolved relationship (issues). I was just feeling mentally and spiritually isolated because all of these environments I was putting myself in.

GS: Now that you’ve been sober for a couple of years, what’s the emotional tenor of the work that you’re inspired to make?

RRL: Sometimes it’s very light, sometimes it’s introspective and moody, sometimes it’s lovesick—it’s all of those things, man. I’ve diversified myself to be less governed by, “Oh, I’m a painter” and more governed by “Oh, this is where I’m at energetically so I’m going to make these things.”

GS: You spent some time living in South Korea after college around 2010. What did you take away from your experiences there and how did it change you as an artist?

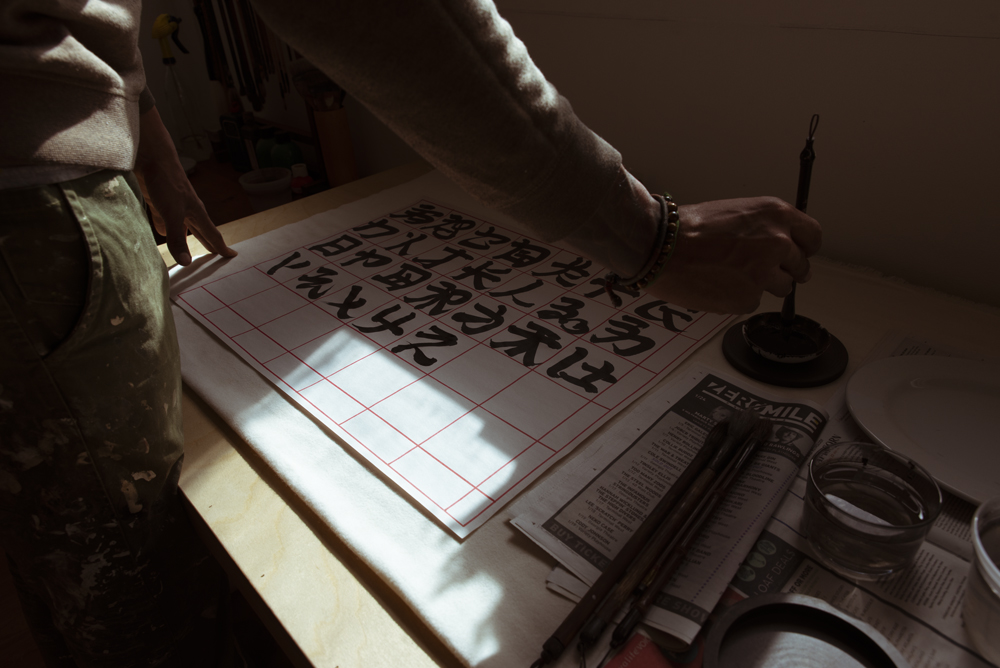

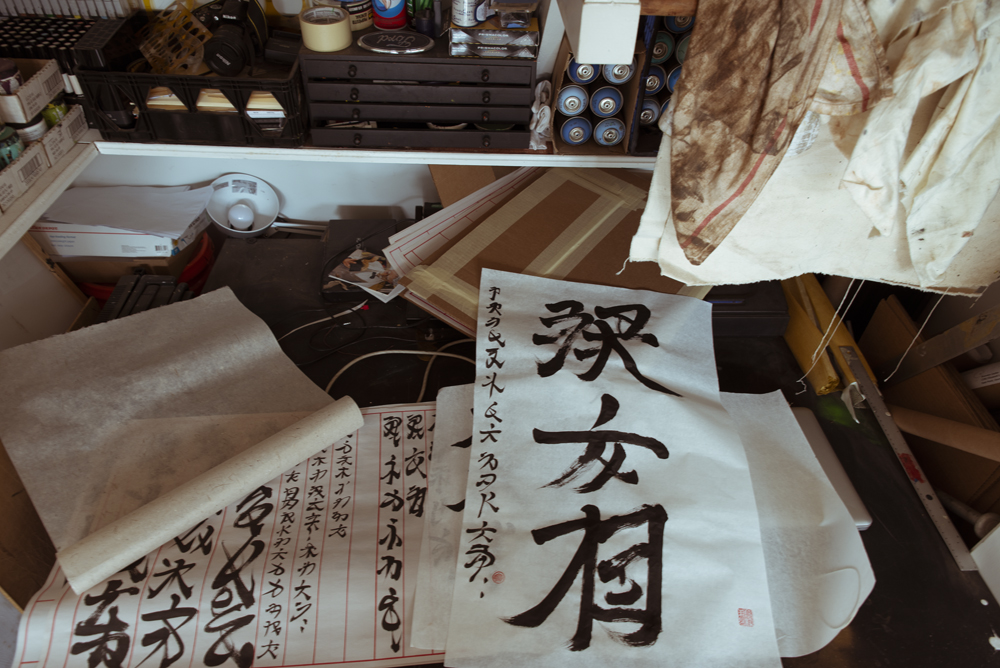

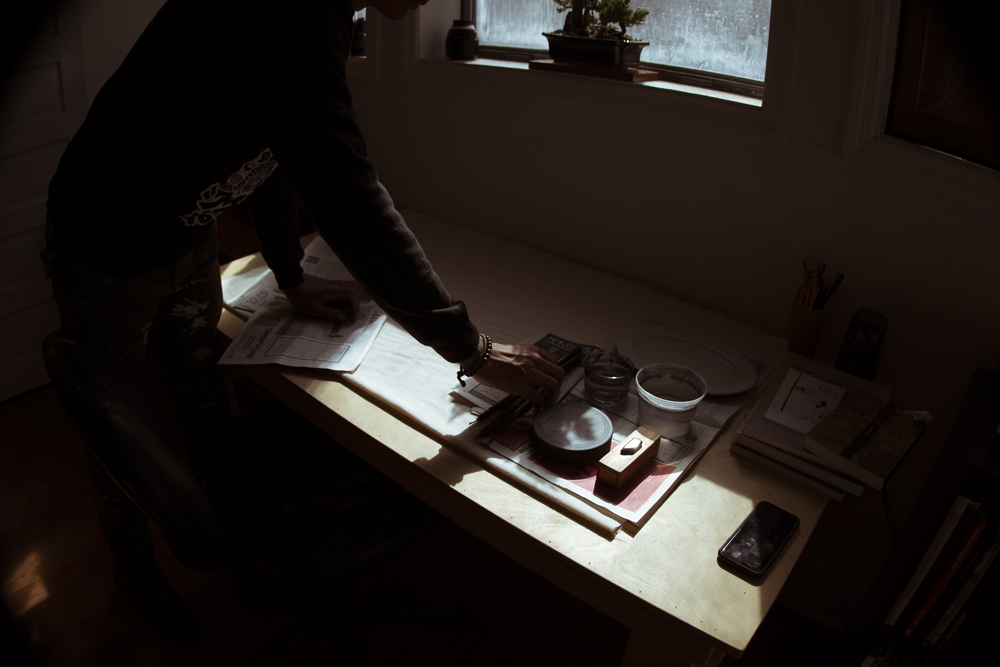

RRL: I think the biggest thing is the writing that I do, the calligraphy. Most of my understanding of design, how to compose a painting, or how to use writing in a piece, it all comes from the graffiti school of thought. Our letters, even in different typefaces, they have a pretty standard way of looking. Going out there was just a refresher to be around a more illustrative language.

I would go to a lot of different art shows and calligraphy shows there. I went to the capital, Seoul, where King Sejong has a huge monument with his statue. He was the ruler who composed the Hangul language, the Korean language. You go into this big gallery and it’s just walls and walls of all this different calligraphy from all over Korea and elsewhere around the world where they write in Hangul.

I already started researching different Asian art forms before I went out there. Then I started going to this section of town called Insa-dong, it’s the capital where all the calligraphy shops are. I would go to this one shop where you walk in and on either side of you there’s papers stacked to the ceiling and brushes and everything. You could barely breathe in there, there was so much stuff everywhere. And there’s this little old guy sitting in the back practicing his calligraphy. He would do these letter forms that were Hangul, but the letter forms themselves looked like people. It was just so sick. I would just go in there and watch him. We couldn’t speak to each other because I didn’t speak very much Hangul and he didn’t speak any English. We just had a nonverbal relationship, which is kind of cool and different. I would just go in there and absorb.

A similar thing happened at this temple. I went in there and this woman was in there painting these old Buddhist meditation paintings. It’d be like a large Buddha in the center and then all around his head different forms of Buddha. I’d go in there and look at her stuff. I couldn’t paint with her because I’m not Buddhist, but I would go in there and have tea with her. We had a similar thing where for the most part we would just kind of look at each other and understand what was going on.

Things just really started to seep into me. I wrote out all of the English alphabet and looked at how they were structured. We have diagonals that go in both directions, horizontal lines, vertical lines, half circles, and whole circles. I took those forms and then coupled it with the brush strokes and the patterns that I looked at from all the places I was visiting. I started making my character system. Hangul is similar to English where it uses vowels and consonants to make words. Japanese or Chinese, they’re both pictorial languages. They don’t have the same makeup as English. I could have been anywhere else, but I think the Korean language and how it’s composed, being similar to English, caused me to go down that route.

GS: In addition to spending extended time in South Korea, I’m also curious how your childhood and teenage years influenced your art. You grew up in a biracial family in Atlanta. How did growing up as a biracial child in the South influence your creativity and artistic output?

RRL: Super heavily. I’ve actually been thinking about it even more because I got a lecture that I’m about to do. You know, a retrospective or currentspective. I don’t know if I’m old enough to retrospective. (Laughs) Growing up biracial, you’re inducted into a way of life where it’s like, I operate on two planes. I identify as one singular plane, ‘cause I can’t wake up and be like, “I’m white today.” (Laughs) I’m always black. But in that, the singular thing that I identify with, growing up I wasn’t accepted because I was light. On the other side, I was fighting every day because I was black. Because of that, you walk this weird duality.

Also, as you grow older, for me, my features were even more ambiguous. I could go for black, Latino, Asian, all these things—except for white, I couldn’t go for that. (Laughs) Because I have that ambiguity, I think it crossed over into my work where I’m mixing, pulling from this culture, pulling from that one. Not in an appropriation way, but in a very genuine, embodying it fully way. I think it wouldn’t have been as fluid, some of these transitions that I’ve made, if I hadn’t come from a background of being both but none at the same time.

GS: It seems like in a way, having ambiguous and difficult to categorize features gave you a certain level of comfort in experimenting with different cultures outside your own. Am I reading that accurately?

RRL: Yeah, you are. I can’t really speak for the white perspective just because I don’t live that every day. But I do think that if you grow up in a society where it’s black community only or Asian community only, there’s a good chance that your perspective is gonna be completely surrounded within that. With that comes all the stereotypes that you’re supposed to enact or the clichés that you’re supposed enact. And it’s sometimes looked down upon if you bridge outside of that. For instance, I don’t know how many times growing up I’d hear, “Oh, you talk white,” or “Oh, you like to go camping? That’s white (stuff).” (Laughs) And in reality it’s like, nah man, people are diverse, they’re complex, they have different facets, and they enjoy different things.

I grew up in very much a black upbringing—the type of music I was exposed to, the type of family unit I had. But I also went to NASCAR races with my dad. I also went to monster truck races. I listened to classic rock. I was the only black kid in a Boy Scout troop all the way up until I was 18. All these quintessential white only things, you know? I have that, but then I’m very much a black man and my worldview is very much from a black perspective in a sense. But then, from the outside looking in, people would think that I was Asian of some sort to the core. That’s just one of the things that I’ve cultivated and researched and lived to a degree because I lived in Korea.

GS: Another unique influence that shows itself through many references in your studio space is the praying mantis. Where does that come from and how is that meaningful to you?

RRL: In undergraduate, right before we graduated, we had a project in illustration class where we had to come up with a self-portrait that crossed up with an animal. I just enjoyed the way the praying mantis looked and thought it was the coolest creature. So I made a self-portrait with the praying mantis. After I did that, I moved to Korea once I graduated in 2010. My mom called me like, “There’s a praying mantis on my doorstep,” or “There’s one on my car,” or “There’s one on the fence.” She called me every other week or so telling me about this new praying mantis that she saw. She took it as a good omen, like it was me or something like that. Ever since then they keep finding their way into my path. They’re pretty rare to see, but they appear in my life all the time. I don’t know, I take it like a spirit animal or something like that.

GS: You’re a very celebrated muralist in Atlanta and you’ve already done a lot of work around the city. I’m curious if there’s a space that’s a dream spot for a future mural.

RRL: To be honest, my view is more set on other cities in our nation and elsewhere. There’s things going on all over the world that put whatever I’ve done here to the back burner because of the scale these people are working on. It’s incredible. There’s something called the Pow! Wow! mural festival that goes to Hawaii, Taiwan, Japan, Hong Kong, Seattle, L.A., all these different places. They do this crazy mural conference where they’ll be X amount of artists and they go all around the city, pick any 10-story building in New York or something like that, and paint the entire face of it. That kind of thing. That’s the kind of stuff I want to do, linking up with people around the country, learning about wherever I’m at and putting that in to the work and doing something on a crazy scale. I’m very appreciative of what I’ve been able to do out here in Atlanta, but man I gotta get out. (Laughs) That’s where my eyes are right now. I don’t really know how to get that, but…

GS: Would you relocate permanently, or do you more envision just working temporarily somewhere else?

RRL: It depends. I really don’t know. I’ve thought about if I have a place here in Atlanta and I just travel all the time, that’d be cool. I’d be into that.

GS: Now that your work was featured in the Black Panther film, do you think the success of the movie will open doors to broader and more ambitious mural projects?

RRL: I really hope so. That was the plan. I was really excited about working on that joint, like thinking that was step one. So far I’ve gotten some commissions off of that work, people wanted me to do stuff that looked like it was from the movie. I’m just hoping that it keeps going in that direction. Not only were those checks really great, it was just really cool to be a part of something like that.

GS: It’s such a historic film and I’m so happy to see the financial success of it too. Not to be callous and by-the-numbers about it, but obviously when something is financially successful, it increases the likelihood of there being more diversity in storytelling moving forward.

RRL: Yeah. And there’s nothing wrong with looking at things from a financial perspective. That’s how the world spins, man. I can enter into that place, bring with it how I feel about whatever we’re talking about on the project, and also get my money. (Laughs) That’s the goal. Working on that project, I was working with people who valued what I did and wanted what I did. There was no penny pinching, there was no nickel-and-diming, there was no cutting in to my creative outlook. It was like, “We want you, we like you because of x, y, z. How much do you want? Oh, you want that? Alright, cool, done.” And that was it.

GS: Wow. It’s so rare to hear about that happening in the creative world.

RRL: Yeah, for sure.

GS: It’s amazing that they had that kind of respect and reverence for what you’re doing to give you that autonomy and treatment.

RRL: Yeah, it’s very hard to come by something like that.

GS: I really appreciate your insight and the amazing work that you’re doing with visual art. Thank you for taking the time out of your day to break it down and go deep into your creative process. This has been such a great talk.

RRL: Oh yeah. I appreciate you even being interested and being enthusiastic about it.